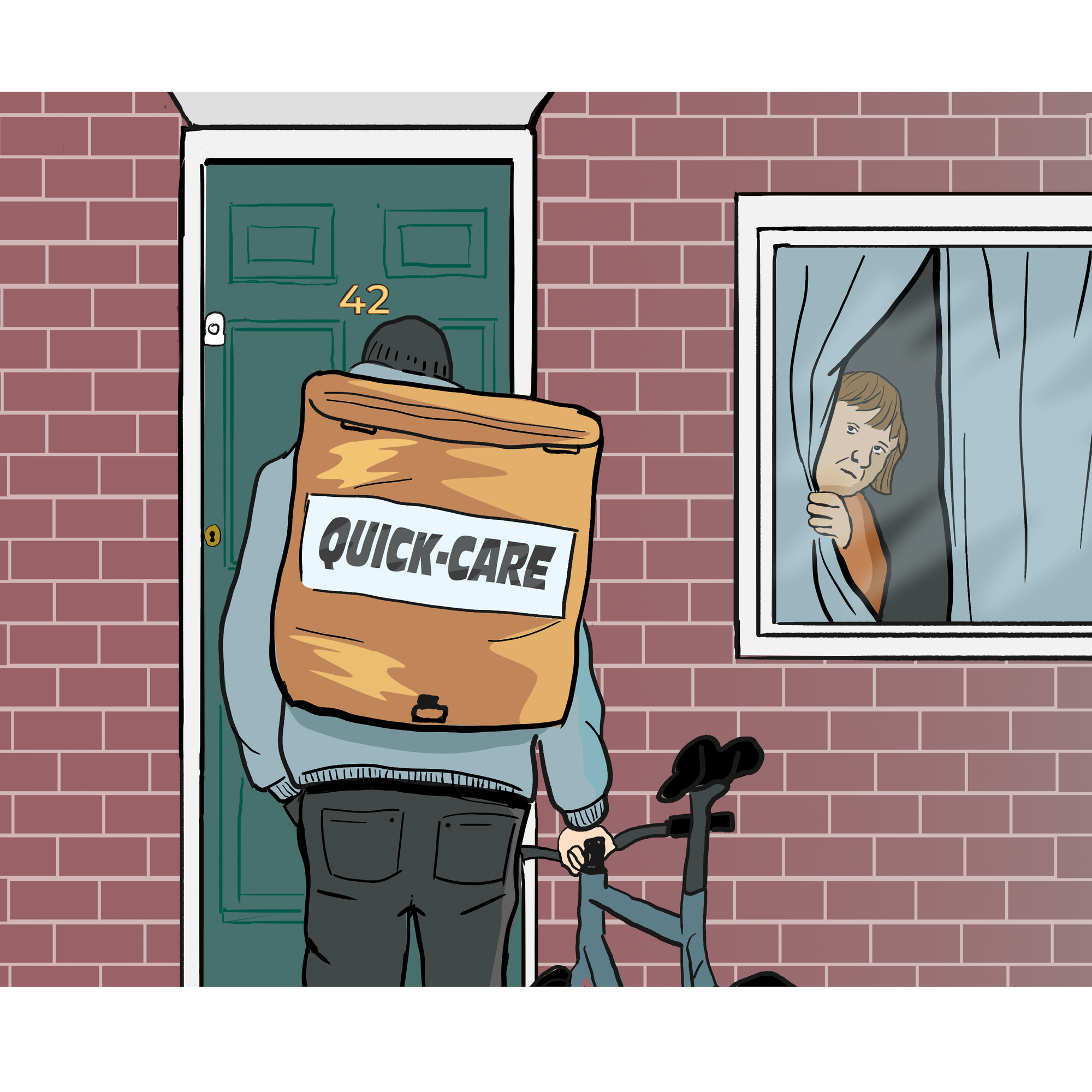

Bringing an end to Deliveroo-style care

The scenario is now familiar to most of us who have ordered anything online. You need something - a gift, a takeaway - and you click through options on a screen before you arrive at your choice and click order. Then, after a specified amount of time a person arrives at your home with (hopefully) the thing you ordered.

Casting your mind back to the last time you did the above, do you remember much about the person who delivered to your door? Would you remember their face in a crowd? Did you catch their name or learn anything about their background?

For most of us, the natural response to the above questions would be along the lines of ‘no, of course not!’ The transactions are accepted as impersonal, fleeting and totally isolated from one another. As nice as it might be to be on familiar terms with the person leaving a box on your doorstep, it’s not an expectation of either side of the exchange.

Now imagine that the ‘thing’ being ordered is not a meal, or an item but your care. But it’s not even an order that you have made: someone you have never met in an organisation you’ve never heard of has been given a bullet point breakdown of what your needs are, and has ‘packaged up’ some of those needs (getting in/out of bed, going to the loo, getting washed and dressed) and ordered someone in their employment to ‘deliver’ that specific ‘package’ of care.

Most would expect to be on familiar terms with whoever turned up at their door to support them in such a personal way. In fact, most of us would hope that we had some sort of say over who that person was, and feel confident that we could build a trusting relationship with that person over a period of time. However this is not the case for many people experiencing care.

It is increasingly the case that care workers are distributed care tasks in the manner of someone working for Deliveroo: some account might be taken of their location, but based primarily on their availability, a worker will be allocated a packaged care task and asked to deliver it within a certain time slot, with other tasks ready for them when that slot has elapsed. They will have little control over the matter, no attempt will be made to make introductions or determine whether a relationship can be built, and no account will be made of the wider networks of support that the person may already exist in.

If this sounds like a strangely impersonal way of delivering something so personal, then that’s because it is. Not only does it treat the individual looking for care as though they are isolated from the community or networks they are a part of, but the care worker is treated as a tool - a solution to a problem.

What effects does this have? Perhaps the biggest hidden cost of organising care in this way is how it takes no account of the importance of care as a relationship. Fundamentally, most of us have an experience of caring or being cared for. In small ways that we are normally unaware of, we each do or say things in our day to day lives that could be considered acts of care. A conversation about how our week has been. A meal cooked for someone. All of these are acts of care.

While some of us will practise random acts of kindness to strangers, more often than not these acts rest on what our relationship is with a person. How well we know somebody, what we share agreement over, what our joint interests are: all of these factors and many more can determine what we feel comfortable with when it comes to giving or receiving care.

Without that relationship, without that respect and understanding, care becomes impersonal. Acts of care are reduced to a few details printed on a sheet of paper. The outline of what is needed is there, but nothing is ‘coloured in’. Having little to no relationship with the person you are caring for or receiving care from can mean missing out on many elements that can bring real quality of life.

Sometimes, this can be the difference between life and death. A care worker who knows you well will notice if things are awry or amiss. The early signs of sepsis can be mistaken for the symptoms of dementia combined with a cold. If you have a diagnosis of dementia with diabetes people who don’t know you won’t recognise your hypo or hyper symptoms until you’re pretty far gone. Trusted relationships save lives.

It is with this important truth in mind that Equal Care focuses on the relationship between caregiver and care receiver. And we allow both sides of the care relationship to choose: it’s a mutual decision to say yes to the support. For workers, this means the opportunity to build lasting, fulfilling caregiving relationships rather than being asked to rush between lots of different people day after day. Those who are looking for care or support get to learn about workers’ interests, skills and experience before agreeing to the match.

By understanding and building trust with everyone involved in the care relationship, we can see beyond the individual care needs that might otherwise be ‘itemised’ by other care providers and turned into a transaction - a problem to solve, a thing to deliver - and instead recognise care as personal again. And it is by giving both caregivers and care receivers the opportunity to create lasting, respectful relationships that they are in control of, that we can slowly eliminate Deliveroo-style care provision and prioritise quality of life needs.